ha ge yama mi ta i 禿 げ山みたい Something Like a Bald Mountain

The first screening of Something Like a Bald Mountain was held in a village in the vicinity of the film’s location. The screening was attended by residents from the west side of Lake Biwa, and followed by a discussion. This website responds to the feedback and conversation that arose from that evening.

A fragmented form of presentation is employed here, one that draws on the notion of landscape. Preserving its integrity by hosting numerous energy cycles, a landscape, nonetheless, is hardly a continuous form. When a film is ‘infected’ by such eco-realism, its narrative continuity cannot but shatter, leaving the filmmaker and viewer in front of scattered images, sounds, voices and texts that cycle the energy of interpretation between each other.

『禿げ山みたい』の初回上映会は撮影場所近くの集落の村で開催された。琵琶湖の湖西に暮らす住民達が集まり、上映後は談議に花を咲かせた。この サイトはあの夜いただいたフィードバックや、参加者の質問への回答として読んでいただきたい。

今作品は森の山水の象徴を盛り込んだ断片的な表現法を採用している。いくつもの生命サイクルを宿しながら自己保全する山水は恒久性とはほど遠い 環境だ。このようなエコリアリズムに映像作品が感化されると、ナラティブの連続性は打ち砕かれ、映像の作り手と観客は相互間の解釈のエネルギーを 循環させる断片的な映像、音声や文字の前に立たされるのだ。

We asked Professor Taki questions at his office. He explained in detail why urbanization increases the risk of flooding and how the mitigation of these risks impacts the ecology of rivers and makes floods even more dangerous. In Japan, rivers always flow from mountains to water bodies, so an alteration of the water regime leads to cascading effects across diverse ecosystems. Professor Taki’s contribution to ecological politics is his study of kasumi-dikes and if they can be used as means for people to coexist with floods. After his introduction, we visited places where kasumitei are located. Nowadays, it is quite hard to recognize these dikes, even while walking directly at the riverbank. Not surprisingly, only a few residents have retained their knowledge of them.

私たちは滋賀県立大学の瀧健太郎准教授に取材し、彼はなぜ河川地帯の都市化が洪水リスクを拡大させるのか、そしてそのリスクを緩和する試みがど のようにして河川の生態系を影響し、逆に水害のリスクを高めるのかなど事細かに説明してくれた。日本の河川は山から水域に流れるので、水環境の改 変は多様な生態系に段階的に影響を及ぼす。瀧教授は霞堤が人と水害の共生につながる可能性について研究を続けながら環境政策づくりに関わってい る。お話を伺った後で、実際に霞堤がある現場を見せてもらった。現在はほとんど認識されなくなっている霞堤は川岸を歩いていても気づかないことが 多い。なので、霞堤について知識を持っている地元住民も今では少数だ。

We met a fisherman at the shore. It was a chance encounter, we watched carefully. We were simply observing him fishing: how he throws the net into the water, how in his activity skill relies on chance. After the demonstration, his net transformed itself into a representation of a technology to embrace chance rather than subordinate it. Isn’t kasumitei also a technology with which people embrace floods?

水辺に漁師の男性の姿を見かけた私たちは、しばらく彼の動作を観察してみた。水に網を投げ入れ、その動作は、偶然に委ねられた能力の実証だっ た。漁師の網はまる、で偶然を従わせるのではなく包容する技術の一例にも見えた。霞堤もまた、人間による洪水を受容するため技術と言えるのではな いだろうか?

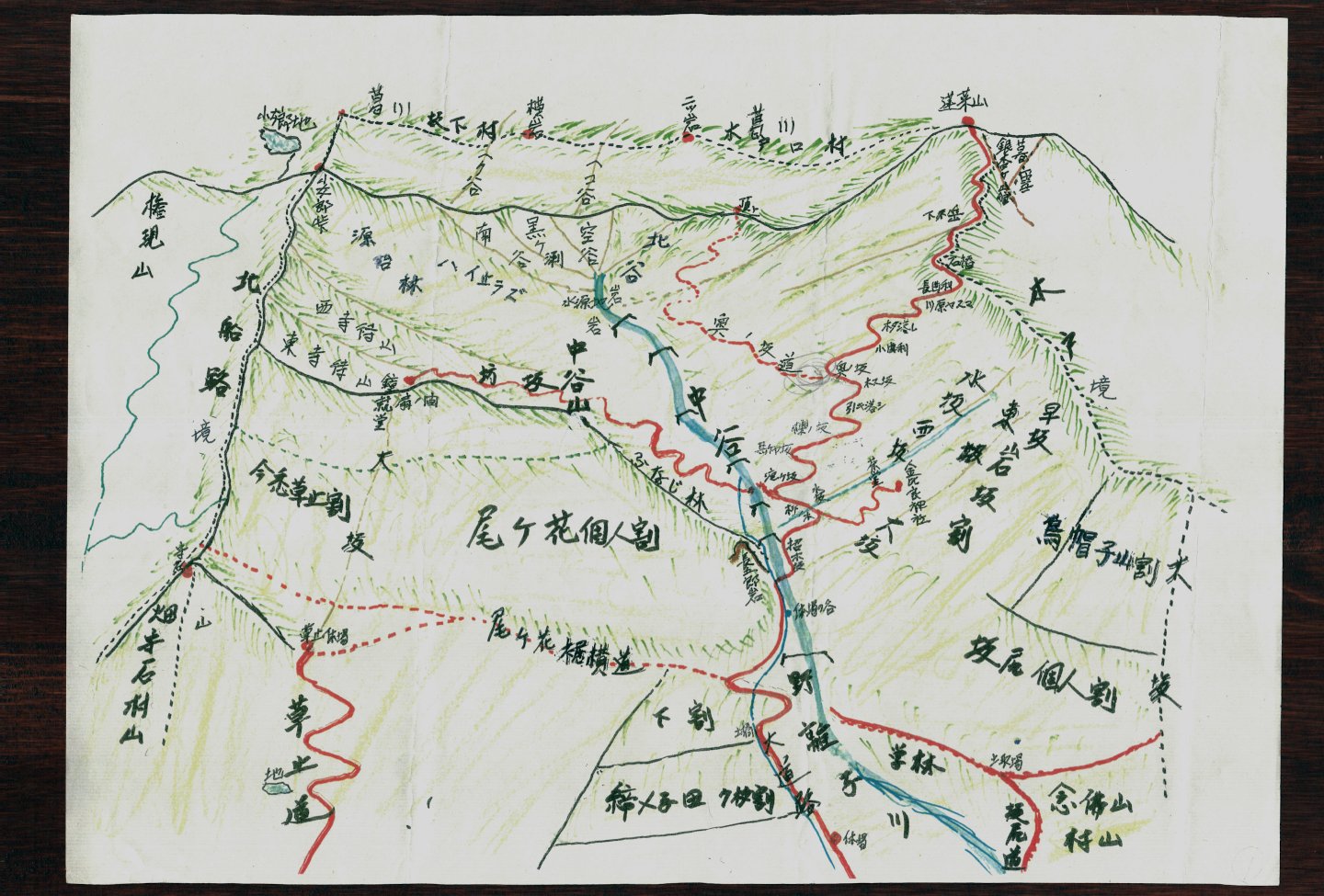

Following the shoreline between the steep slopes of Mount Horai and the western side of Lake Biwa, we came to Moriyama Village. There we searched for a place where one could actually observe the link between the mountains and the lake. We shall look at the sediment transfer, Prof. Taki explained. The beautiful Moriyama stone, he told us, moves to the surface with the sediment; it used to be procured along the river after landslides. These stones were popular for designing gardens and were sold throughout the region, including Kyoto. Later, Ishizuka Sadajiro showed us a wooden cart, used to gather these stones on the slopes of Mount Horai.

蓬莱山の急な斜面と琵琶湖の湖西の境目の水辺を進むうちに守山の集落に入った。私たちは山と湖の交差するところを実際に目視できる場所を探 した。堆積物が移動するところを瀧教授が案内してくれる。美しい守山石は堆積物と一緒に表面に押し出され、土砂崩れの後で川のほとりで収集さ れていたそうだ。守山石は庭作りによく使われ、京都をはじめ関西地方で幅広く流通されていた。ここで石塚さんが蓬莱山の石を集めるために使わ れていた木製の手押し車を見せてくれた。

A truck drove uphill almost to the top of Mount Horai, it’s engine struggling to overcome the gravity of the mountain road. The same gravity causes the Noriko River to rush in the opposite direction through a sequence of rapids. In the typhoon season, water obtains enough power to push giant boulders around and grind stones into sand. The force of the flow causes minor “environmental disturbances” and alters the riparian zone. Periodical alteration of the riverside environment results in a dynamic patchwork of micro-habitats in which a diversity of plants and animals are established.

Variability of the river and riparian morphology — or simply the river’s body — cannot be fully mapped or known, since it is a rapid becoming. Observing the river, studying its fluid mechanics and pulses of disturbances, became an exercise in an embodiment technique: Align your breath and bodyweight so you can move smoothly and project the water’s path into the camera. Interrupt. Repeat. Try to construct the rhythm of fluid currents and the stones resisting them.

一台のトラックが蓬莱山の頂上近くまで登っていた。山道の重力に一生懸命に逆っているように見える。この重力が、トラックとは逆の方向に激しく 流れる野離子川の水流を作っている。台風の季節になると水の激しさは増し、大きな岩や動かし、小石を砂にと粉砕していく。川の勢いでが環境に小さ な「乱れ」を起こし、河岸の形が変化される。川岸環境の周期的な改変は、ダイナミックなパッチワークのような動植物の生物多様性を構築する。

変動的な川の形態(川の体幹、とも言えるだろう)はとめどなく変形するため、正確にマッピングする事も把握する事もできない。川の流動的な機能 性や脈打つような流れの中断の観察は一つの体現の練習となる。呼吸と身体の重心を整えてなめらかな動きを意識する事で水の流れをカメラに集中させ る。中断と再発のくり返し。水のリズムと流れに抵抗する石の再現を試みる。

Long ago, people captured part of the Noriko’s water in a channel for irrigation. Using stones, they created a semi-natural environment similar in its properties to the river’s own. Evidently, the secondary metabolic circuits established atop of the channel’s primary function are responsible for the similarity.

昔の人々は野離子川の流れの一部を灌漑するため、石を積んで河川環境と似たような半自然環境を作り出していた。その類似性は水路の主要機能 の上に成り立つ循環経路の副機能から生じている。

Thinking about Prof. Taki’s introduction, we wondered — all in our own way — how the different forms of consciousness regarding “natural disasters” may look like? Descending along the Noriko River, we encountered a series of enormous concrete dams and embankments built in the 1970’s and 80’s to prevent sediment from flowing down the river. The constructions provided security to the newly developed areas of the village, its train line and roads, at the cost of damaging the riparian ecosystem by “freezing” disturbances and breaking continuities. Many authors have drawn critical attention to the fact that the concrete industry and public works reached abnormal scales in Japan, as they were instrumental for postwar economic growth.1

Not far from the disaster-prevention installation, we found Chogoro-iwa, an enormous rock, admired by the residents of Moriyama. Perhaps this rock represents another way of being conscious of natural disasters.

瀧准教授の説明を反芻しながら、我々は自然災害と呼ばれる現象に対する意識の違いについて考えてみた。野離子川の川沿いを下ると、河川に流れ込 む堆積物をせき止めるために、1970年~80年代に建設された巨大なコンクリートのダムや堤防が並ぶ場所に出た。ダム建設の影響で地域の治安や 鉄道や道路などは良くなったが、その代償として河川の生態系の「乱れ」が遮断され、サイクルが中断されてしまった。戦後日本の高度経済成長期の後 押し役となったセメント業界や公共事業だが、その異常なほどの成長規模にこれまで多くの研究者が警鐘を鳴らしてきている。1

防災の名目で建てられたダムからそれほど遠くない地点に、長五郎岩という大きな岩を見つけた。守山集落の住民達に親しまれているこの岩もまた、 自然災害への意識や対策の別のあり方なのかもしれない。

Further downstream along the Noriko River, the satoyama area begins — wooded hills behind the village. Prof. Fukamachi showed us how to read the history of little disasters, or environmental disturbances, through the composition of the forest. In fact, disturbances such as small landslides, typhoons and coppicing for firewood create a mosaic of different micro-environments, bright and shadowy areas, where the photosynthetic habits of diverse forest species are satisfied.

野離子川を下って行くと村の裏の里山が見えてくる。深町准教授が森林の構造から「小さな災害」と呼ばれる環境変動の史跡を読み解き方を教授 してくれた。土砂崩れや台風、薪づくりの萌芽更新などの乱れは森林の多様な生物の光合成機能を満たすミクロ環境や日向と日陰をモザイクのよう に連なっている。

Together with the river’s water, we descended from the mountaintop into the village. We were lucky to see the Hiyoshi-Taisha Festival, which takes place a few kilometers south of Moriyama. The dramaturgy of the event directly echoes our way up and down Mount Horai. Not surprisingly, a flow of people descending from the mountaintop to the shore reminds us of the waters of the Noriko River. Similar to a mountain river, the procession flows downhill, passes the village and reaches Lake Biwa.

In the book Bodies of Water, we read: “Our concepts are already here, semiformal and literally at our fingertips, awaiting activation.”2 In our context, the river becomes a figure and a tool to think of people’s embeddedness into the environment; as a concept it has been activated by means of the ritual.

Animistic religion and local culture are precise in how they address the natural environment. The anthropologist Andrea DeAntoni provided more examples. On the shore where the final stage of Hiyoshi Taisha Festival takes place, he read a fragment from Miyake Hitoshi.3 From what we heard, we understood that the relation between mountains and water bodies has been taken as a model for many religious practices, while the people’s space has been conceived as a negotiation between these two cosmological poles.

私たちは川の流れに沿って山頂から集落へと下山した。この日はたまたま守山岳から数キロ南の地域で行われている山王祭を見ることができた。祭り の演目は私たちが辿ってきたばかりの蓬莱山のルートを再現していた。山頂から水辺まで降りてくる人々の動きは野離川の水流を彷彿とさせる。山から 湧き出る川のように流れは村を通り過ぎ、琵琶湖にたどり着く。

Bodies of Water という書籍に、こんな文章があった。『私たちの概念は既にここにある。少し儀礼的な感じで、文字通り手の届く距離で活性化されるのを待っているのだ。』2 当作品の文脈では、川は身体的なものであり、人々の自然との親和性を考えるツールとなる。儀式などの風習を通して活性化される概念なのである。

アニミズム(地霊信仰)や地方風習などから来る言い伝えは自然環境との向き合い方を具体的に提唱する。琵琶湖のほとりで山王祭が終盤に差し掛 かっていた頃、人類学者のアンドレア・デアントニはて宗教学者・宮家準の一節を読み上げてくれた。3 内容をかいつまむと、山々と水の交わりはいくつもの信仰的な儀式などのモデルとなっており、人間が暮らす空間はこのふたつの世界軸の狭間にこしらえられた、と理解した。

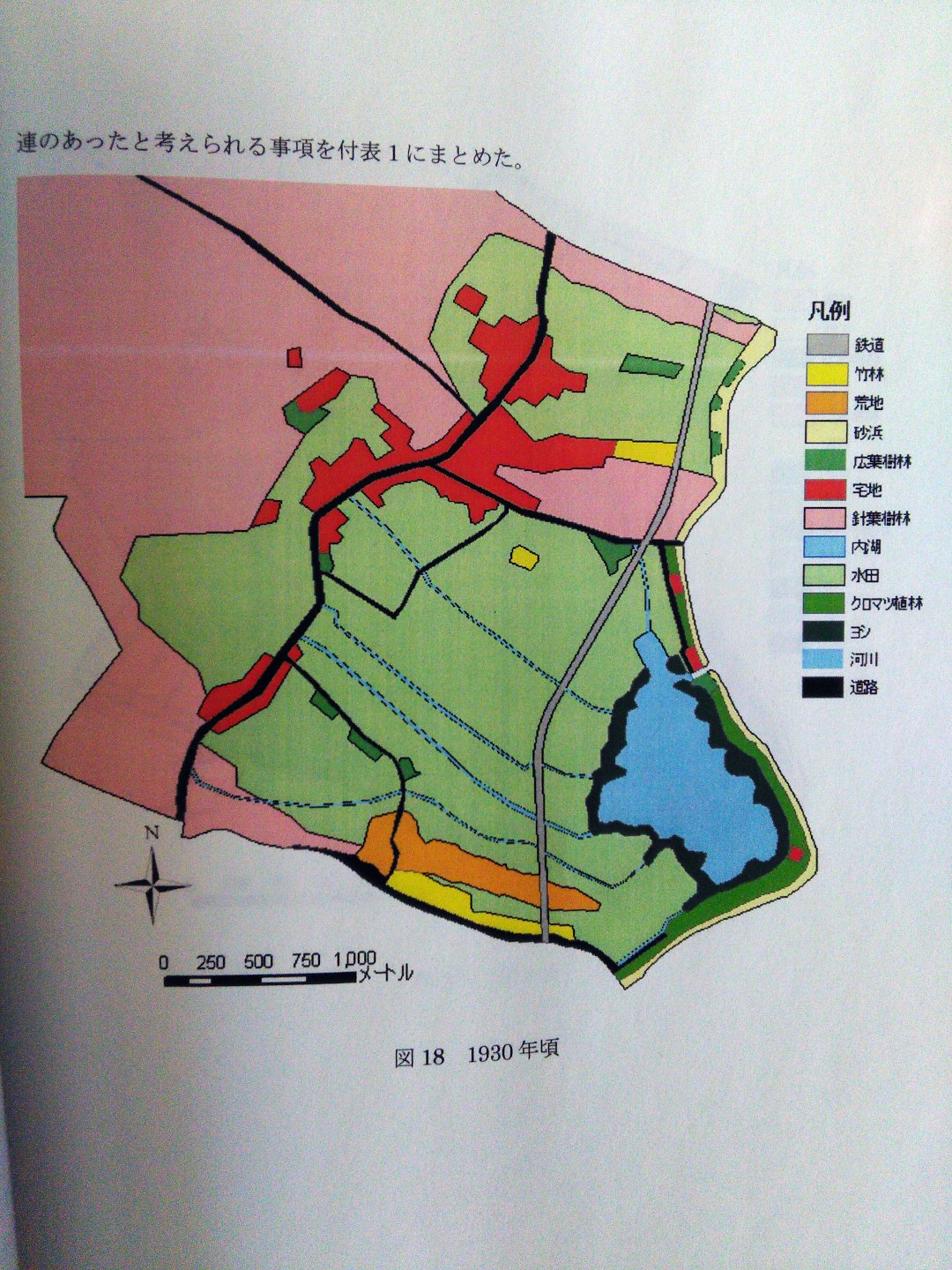

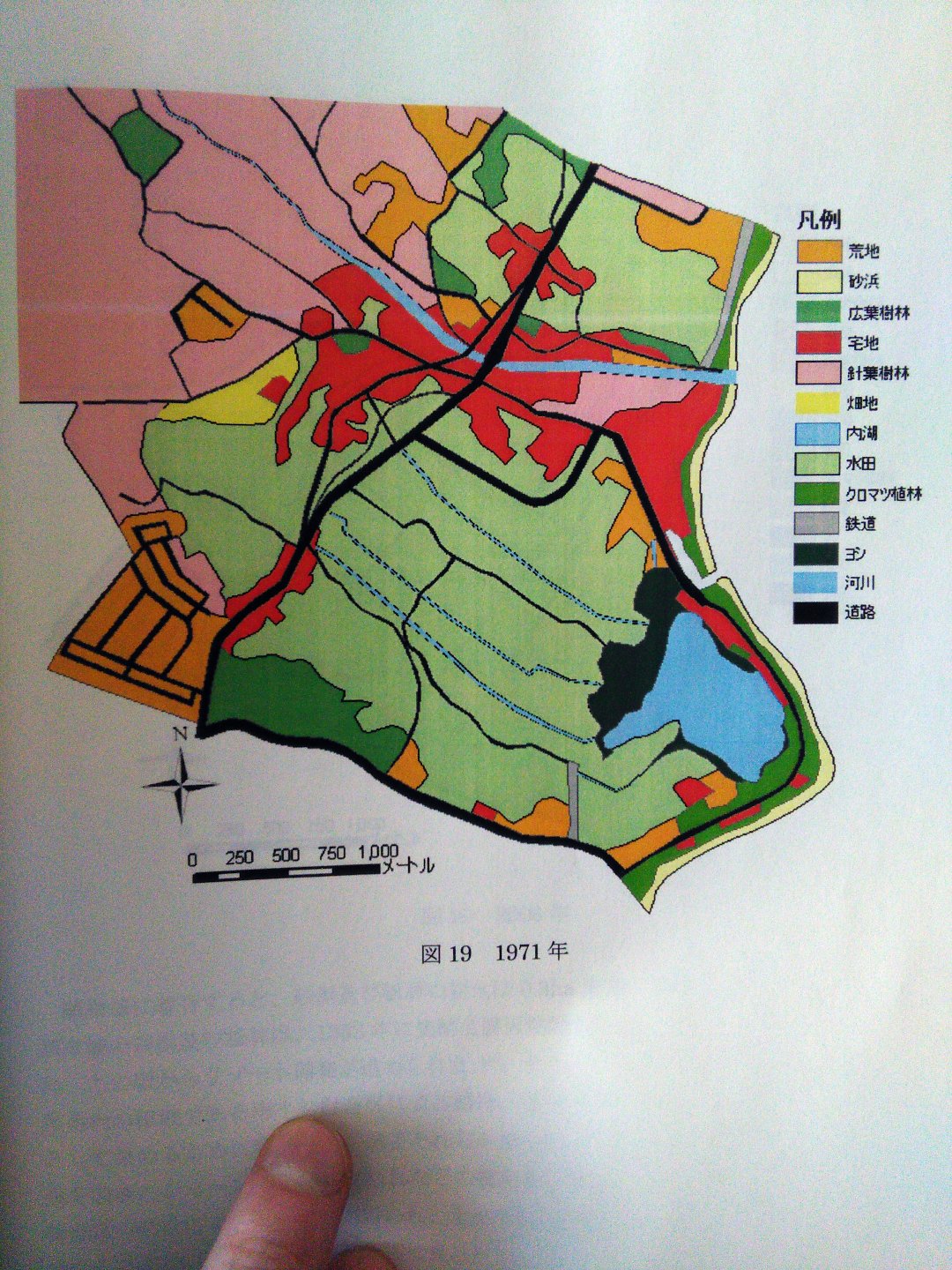

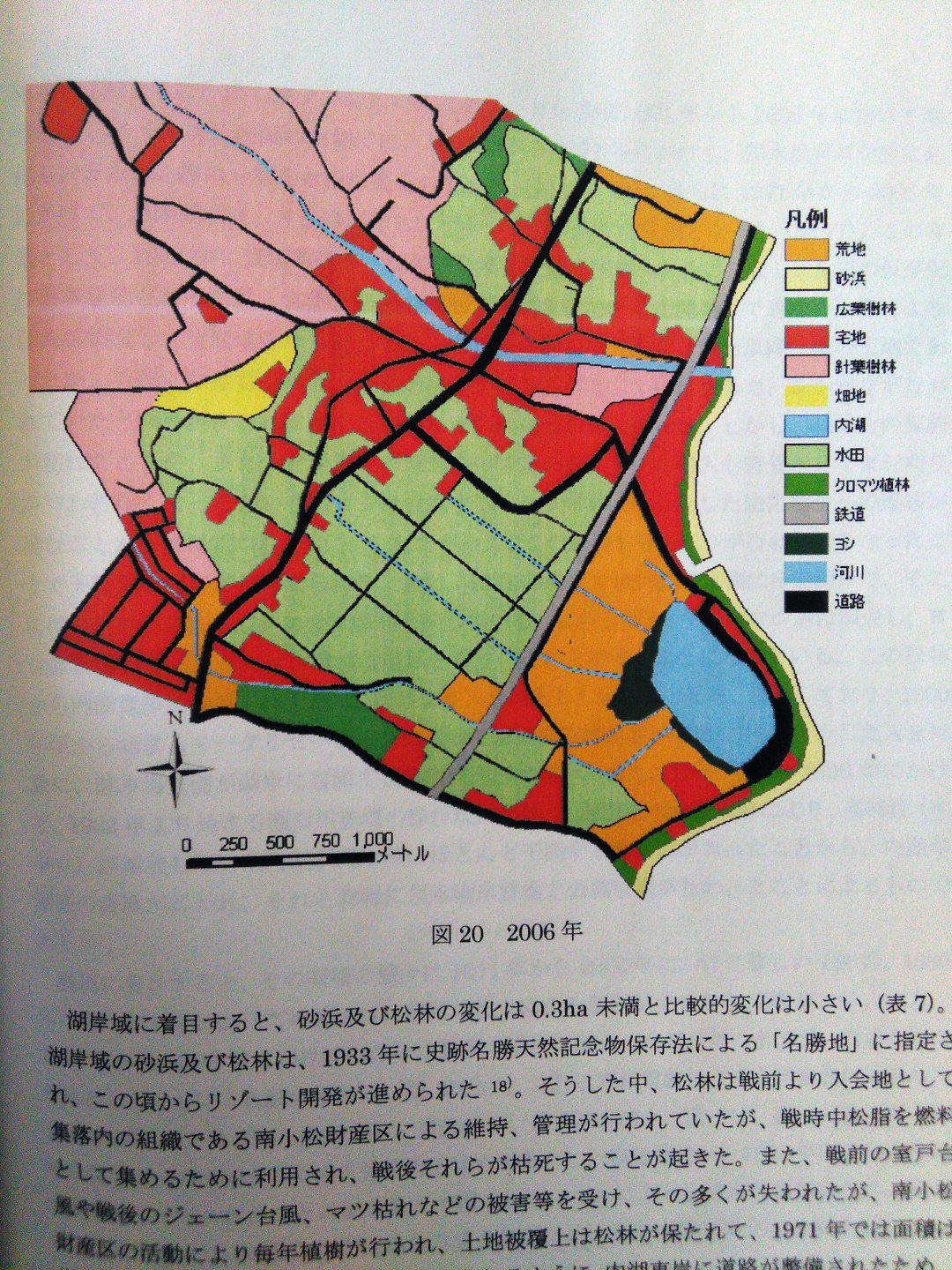

Rice cultivation depends on the element of water and the element of earth to thrive. At the shore of Omimaiko and Lake Biwa, we stood right between these elements. From interviews with local residents and an investigation of historical land use, we learned how the community has been changing its relationship to its environment.

耕作の実り具合は水と土に左右される。近江舞子水泳場で私たちはまさにその二つの要素の間に立っていた。地元住民への取材や、歴史代々の土地の 開発法の調査を通して、この地域の人と自然環境の関わりがどう変わってきたのかを知ることができた。

Studying the River,

Learning From the Water

I have spent roughly a year following the work of a group of researchers and students who investigate communal responses to natural disasters and technologies for ecological disaster risk reduction (eco-DRR) around Lake Biwa. While I was learning from the researchers, the researchers were learning from the stories of local residents, and the stories originated from the people’s experience of daily interaction with the environment. Collective learning is an interesting process in its own right, as the shared experience leads to different results for every participant. Hence, knowledge, facts and information are only parts of the valuable outcomes of the collective research process. For example, before one learns something, (s)he develops an interest in the subject. The attention that is created is as important an outcome as the knowledge itself. Making a film—making an image of something—is first of all an exercise in paying attention. And as soon as some attention is given, it provokes attention in response. Drawing from my experience of participation in various research projects, I think that a researcher or a filmmaker, despite the particularities of their practices, becomes entangled with the local community precisely because of this exchange of attention. This basic exchange underlies the creation of values: attention associated with a particular person becomes a perspective of appraisal, an attitude; becoming aware of the difference of another’s perspective leads to a change in your own attitude. As a filmmaker, I am interested in this dimension of learning, which underpins and parallels the formation of knowledge per se.

Ancient Chinese philosophers, such as Laotzu and Chuangtzu, formulated their philosophical knowledge by observing rivers and the qualities of water. Mountains and rivers appeared to them as self-governing entities; through the observation of the river’s way of living we can understand its ethics and use of power. In other words, what the ancient Chinese philosophers wanted to transform into knowledge—what they paid attention to—were the attitudes of rivers and the habits of water.

For example, Laotzu recommends to observe how water follows the river’s path and to use your power and energy in a similar way, thus formulating the principle of wu-wei: “The world is ruled by letting things take their course. It cannot be ruled by interfering.”1 Are not the kasumitei an example of the medieval engineers learning how to live with the rivers, to govern them without governing by letting them follow their habit? To do something in accordance with wu-wei is therefore considered the achievement of the aim through acting in accordance with the propensity of things.

In the context of modern disaster prevention engineering, water is understood as an object of governance because it possesses a destructive potential: the purpose of managing a river is to counteract the water’s force. In my opinion, this represents a distinctly modern concept of force, which defines force as a potential to exert violence. In the view of ancient philosophers, water, corresponding to yin, is also a force, but of a different kind. Because water can take any form given to it, and, without any additional effort and utilizing only its own weight, can pass through even the tiniest of fissures, it can be considered the force of perceptivity, a creative yet passive force. Using the modern language of technology, one can say that the attentiveness of water teaches us to use our energy efficiently, to achieve more by doing less. “Practice non-action. Achieve without doing,”2 recommends Laotzu.

While working on the film, I encountered another fascinating example of learning from the natural environment in the Hiyoshi-Taisha Festival of Otsu City. The festival’s celebratory events are staged in accordance with the path of the river that runs down from the mountaintop, passes the villages with their rice paddies and arrives to its “home”3 Biwa Lake. When I see the image of people flowing down the hill, all wearing white happi jackets, I cannot but think that the observation of mountain rivers must be at the source of the Hyosha-Taisha Festival. A river travels unlike a person: it has not left its source although it has already arrived at its destination. If the river, in following its path, neither leaves nor arrives, then it eternally returns, just as the festival returns every year. Although the river returns eternally, one cannot enter the same river twice, for every time it is different water that flows past your feet.4 In the same manner, the Hyosha-Taisha Festival celebrates the season’s change: “Change and difference is what returns and repeats,” the river tells us.

In a time of serious ecological crisis, we are tempted to search for recipes for living in organic harmony with nature. This seems to be a strange way of thinking, because disagreement and discord are as much a part of the unfolding of ecological processes as peace and harmony. For example, recurrent ecological disturbances such as landslides and floods diversify ecological conditions and contribute to the richness of ecosystems. Just as the satoyama5 is exemplary in articulating the value of human induced ecological disturbances in maintaining diverse ecologies, examples of eco-DRR mechanisms such as kasumitei can articulate the value of rivers and their habits for maintaining healthy ecosystems.

If we compare pre-industrial technologies of disaster risk reduction, which are the focus of the eco-DRR research project, with modern mainstream methods of disaster prevention engineering, it becomes apparent that the two methods reference the two varying conceptions of force described earlier. As the environmental philosopher Marion Hourdequin puts it:

The view of nature inherited from enlightenment puts its faith first of all in human rationality, it emphasizes controlling and planning, directing our lives and shaping the world around us. What is lacking in this view is ... receptivity. Receptivity involves “a capacity of seeing and a tendency of seeing others’ viewpoints … in the favourable light, in which they appear to those others”. As such it is bound up with care and empathy, and with our emotional lives more generally.6

Receptivity is a virtue attributed by Chinese philosophers to water. Paying attention to the attitudes and habits of water allows them to understand what it means to act receptively. Hence, it is not the power to affect that we learn from water, but the power of being affected. It is from water that one learns to appreciate the perspectives of others and to act in accordance with the propensity of the environment.

Kasumitei weirs, stone water channels suiro and shishigaki stone fences—the technologies at the focus of the eco-DRR project—take advantage of the power of being affected by environmental events just as much as they manifest the people's power to affect their environment. Hence, the contemporary value of these old technologies does not stem solely from their efficiency, functionality or durability, but also derives from the fact that they encapsulate a receptive attitude towards the environment. Re-evaluation of these technologies may bring our attention to the necessity of learning from the rivers and water, mountains and stones.

川を学ぶ、水に学ぶ

ほぼ1年かけて、私はある研究者と学生のグループを追いかけてきました。このグループは、琵琶湖周辺の自然災害に対して地域社会の人々が示す反 応と生態系を活用した防災減災(Eco-DRR)を調査しています。私は研究者の皆さんから学び、研究者の皆さんは地域の人々が語る話から学んで いました。そうした話は、人々が日々環境と関わり、そこから得られた経験に基づくものでした。集団的学習は、それ自体が興味深いプロセスです。共 有された経験から、参加者の一人一人が違う結果にたどり着くのです。ですから、知識や事実や情報は、集団的な研究の過程で得られる貴重な成果のほ んの一部でしかありません。たとえば、人は何かを学ぶ前に、まずそのテーマへの関心を育てます。そんな風に、ある事に注意を向けると、その注意そ のものが、知識と同じくらい重要な研究の成果になっていきます。映画を作ること、何かのイメージを作ることは、何よりまず、注意を向けることの練 習になります。そして、何かに注意を向ければ、それがまた新しい注意を生み出します。私はいろいろな研究プロジェクトに参加させてもらううちに、 研究者と映画製作者のどちらも、実践していることの分野は違っても、まさに地域社会の人々と互いに注意を向け合うことで、その地域に深くかかわっ ていくようになるのだと思うようになりました。こうしたシンプルな注意のやりとりから、新しい価値が生まれてくるのです。ある人に向けられた注意 は、物事を評価する視点や姿勢になります。誰かの視点が自分の視点とは違うことに気づけば、自分の姿勢が変わってきます。映画製作者として、私は こうした学びの次元に興味を惹かれます。この学びの次元は、知識の形成そのものを支え、それに寄り添うものです。

老子や荘子といった古代中国の哲学者たちは、川を眺め、水の性質を観察しながら、彼らの哲学的な英知を育んできました。山と川は、古代の哲学者 たちの前に、自らを律する大きな存在として立ち現れます。ですから、川のあり方を観察することで、私たちはその倫理や力の使用を学ぶことができる のです。言葉を変えると、古代中国の哲学者たちが知識に変えたいと願って注意を向けていたのは、川の姿勢や、水の性質なのです。

たとえば老子は、水が川の流れにどのように従うのかを学んで、同じように力とエネルギー 使いなさいと、私たちに勧めています。こうして「無為 」の理念が形作られたのです。

「この世界は、ものごとがありのままの流れに沿うことで成り立っている。干渉しても支配することはできない。」1

霞堤は、近世の技術者たちが川をそれ自身の性質に沿わせることで、川とともに暮らし、川を治めずに治める方法を学んでいたことの良い実例ではな いでしょうか? ですから「無為」と調和して何かをなすとは、その物の性質と調和して行動することを通じて、成果を得るということだと思います。

現代の防災工学の観点では、水は破壊的な可能性を秘めているので、管理しなければならないものだと考えられています。そして、川を管理するとい うと、その目的は水の力に対抗することになります。私からすると、これは明らかに、近代的な力の概念を表しています。「力というものは暴力をふる う可能性があるもの」と定義しているのです。古代の哲学者の見方では、水は「陰」に対応するもので、これも力ですが、少し違った種類の力なので す。なぜなら水は、求められればどんな形にもなり、他の労力を追加することなしに自らの重さだけで、どんなに小さな裂け目をも通過するので、水に は智覚の力があり、創造的でありながら受動的な力があると考えられるのです。現代のテクノロジーの言葉を使えば、水の創造的な注意力は、私たちが エネルギーを効率的に使用し、より少い行いでより多くを達成することを教えていると言えます。老子は私たちに語ります。

「為す無きを為し、事無きを事とし、味無きを味わう。」2

映画の制作中、私は大津市の日吉大社の山王祭りという、もう一つ別の魅力的な出来事に出会いました。これもまた、自然環境から学ぶことを教えて くれる良い教材です。この神事は、山の頂上から流れ下る水路に沿って行われます。この流れは、山頂を出て、田んぼや村を通り、最後に「家」3 である琵琶湖にたどり着きます。白い法被を着て、丘を下って流れる人々の情景を目にすると、山から流れてくる川を眺めて学んだことが、日吉大社の 山王祭の原点に違いないと思えます。川の旅は、人の旅とは違います。川は、その源から離れずに、すでに目的地に到着しています。もし川が、その流 れに沿って出発も到着もしないとすれば、それはつまり、永遠に回帰するということです(ちょうど祭りが毎年巡ってくるように)。川は永遠に回帰し ますが、人は同じ川に二度入ることはできません。川を流れる水はいつも違っているからです。4 同じように、日吉大社の山王祭は毎回、季節の変化を祝います。

「変化や違いは、回帰するもの、繰り返すものなのだ。」− 川は私たちに、 そう教えてくれます。

深刻な生態学的危機の時代において、自然と有機的に調和した生活をするための秘訣を、私たちは求めたくなります。この考え方は、私にとっておか しな物の見方に思えます。なぜなら不調和や不一致も、調和や一致と同様、生態学的過程が展開することの一部分だからです。たとえば、地滑りや洪水 といった、絶えず繰り返される生態学的なかく乱も、生態学的な条件を多様なものにし、生態系を豊かにしてくれます。ちょうど里山が、生態系の多様 性を維持していくうえで、人間が引き起こす生態学的なかく乱にどんな価値があるのかをはっきりと示しているのと同じように、霞堤のような、生態系 を活用した防災減災(Eco-DRR)のメカニズムの例も、健全な生態系を維持するために川がどんな価値を持っているのか、川のどんな性質が役に 立っているのかを、明らかにしてくれます。

Eco-DRR 研究プロジェクトが焦点を当てている、産業化以前の防災減災の技術と、現代の防災工学の主流になっている方法を比べると、力というものについての二つの異なる考え方が示さ れているように見えます。環境哲学者のマリオン・ホアデキンは、こんな風に説明しています。

啓蒙主義から受け継がれた自然観は、何よりもまず人間の合理性に信頼を置いており、私たちの生活を制御し、計画し、方向づけ、周囲の世界を 作り変えることを重視しています。この考え方に欠けているもの、それは、受容性です。受容性とは「他者の視点を、(...)それが他者に現れ る際の好意的な光の中で見る能力、そして見ようとする傾向」に関わるものです。ですから、受容性は、労りと共感、さらにはもっと広く、私たち の感情的な生活と密接に結びついています。5

受容性は、中国の哲学者たちが水に見出した美徳です。水の姿勢や性質に注意を向けることで、彼らは受容的にふるまうことが持つ意味を理解するこ とができたのです。それゆえ、私たちが水から学ぶことは、周りに影響を与えるための力ではなく、周りからの影響を受け入 れるための力なのです。水 は、他の人の視点を受け入れ、周りの環境の在り方に調和して行動することを教えてくれるのです。

霞堤の堰せき、石の水路、シシ垣などは、どれもEco-DRRプロジェクトが焦点を当てている技術ですが、こうした技術は、それが環境に影響を 及ぼす人々の力を表しているのと同程度の仕方で、環境事象から影響を及ぼされる力を利用しています。ですから、こうした伝統的な技術は、その効 率、機能性、耐久性といった面からだけではなく、環境に対する受容的な姿勢を体現しているという面からも、今日的な価値を持っているのです。こう した技術が再評価されることで、川や水、そして山や石からもっと学ぶ必要があると、私たちの注意が喚起されるかも知れません。